Parenting Advice from 1871

And why modern parents probably aren't the most anxious ever

In The Carpenter and the Gardener, Alison Gopnik remarks that the word “parenting” only began to be widely used in the 1970s when the market for parenting experts and their how-to books first arose.1 Before then—so the narrative goes—nobody needed parenting advice from external sources because humans lived in close-knit communities where people had direct experience of childcare before having children of their own. As Gopnik writes:

For most of human history, people grew up in large extended families with many children. Most parents had extensive experience of taking care of children before they had children themselves. And they had extensive opportunities to watch other people… take care of children. Those traditional sources of wisdom and competence—not quite the same as expertise—have largely disappeared.2

It was only when people started working more outside the home and for longer hours; delaying parenthood; and moving away from their extended family networks that a gap in knowledge and experience emerged which parenting experts could plug with books, equipment and—today—Instagram reels.

This idea was recently repeated in Jonathan Haidt’s Anxious Generation, and I have since encountered it in various places on Substack. But, as an historian, I am wary of fall narratives such as this one, in which the past is presented as a kind of Eden. We humans used to have it so good, until we foolishly ate from the Tree of Knowledge and now find ourselves worse off.

Moreover, I work in a library and several parenting advice books from as long ago as the 1800s recently came across my desk. Flicking through them, I found some surprisingly familiar talking points and thought they might be of interest to the parenting community on Substack. So, let’s take a look!

The Origins of “Parenting”

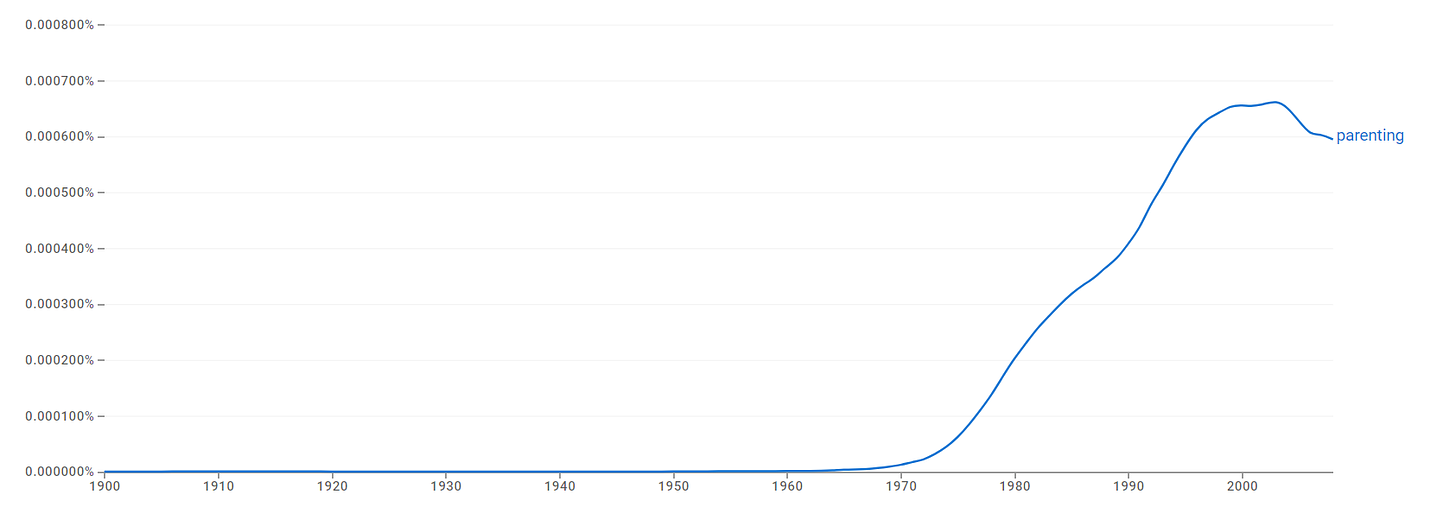

First, some remarks about the origins of the word parenting. Gopnik cites the Merriam-Webster Dictionary which, at the time her book went to print, listed the first recorded use of parenting as 1958.3 A look at Google’s Ngram viewer seems to confirm the picture: instances of the word parenting rise rapidly from the mid-seventies onwards.

But the coining of a term rarely marks the origin of the thing itself. We invent words to describe what is happening or already in existence around us. And the likely reason the word parenting becomes popular in the 1970s is because it represents childcare as a gender-neutral activity. Previously, it had been considered women’s work and so older parenting advice manuals tend to be called things like Advice to Mothers or Guide to Mothering.

I have chosen two such texts to look at. First, Maidenhood and Motherhood by one Mrs. Robert Stephenson, published in 1887; and second, The Physical Training of Children by Pye Henry Chavasse, published in 1871.

Maidenhood and Motherhood (1887)

Maidenhood and Motherhood is a thin, pocket-sized book containing transcriptions of two lectures given by the author—who’s name is given only as Mrs. Robert Stephenson. She evidently belonged to the Temperance movement, with both lectures admonishing drinking houses and stressing the importance of a life dedicated to Christ.

The lecture on motherhood begins with a reflection on perfection. Stephenson admits that she has never met a perfect mother, but sketches a picture of what such a woman would look like. Perfect motherhood is preceded by a healthy childhood and adolescence:

My perfect mother has excellent health. When she was a girl she had plenty of exercise and nourishing food; and she never tried to improve her figure by drawing in her waist or allowing pressure upon her breasts; she used to work in the day and rest at night, and not… stay up at night in the gaslight at places of entertainment.4

When this young woman becomes a mother, her ‘strong nerves’ mean she is available to her children at all times and able to entertain them all day long:

My perfect mother… never has a headache, and her nerves are strong, so she doesn’t at all mind about the noise children make; and she is able to give them the great advantage of their mother’s company nearly all day long. When two or three of them want the same toy, she quickly find some new source of amusement to engage their attention; she is always at hand to dry up tears and comfort sorrows, and her children never hear that their mother is too tired.5

As a result of this attentiveness, Stephenson writes, “her boys and girls never have to go and play in the streets”.6

Stephenson fears that the young people of Britain—especially girls—are falling into sin:

I know that with young women it is very hard to reclaim them once they have fallen. The first step into sin quickly leads to the second… soon they are at the bottom of the ladder.7

The best chance to counter this is adequate training in childhood to “mould their characters right,” in order that we might “see our boys grow up to manhood and our girls to womanhood in absolute purity and chastity.”8

Stephenson also laments the increasing tendency of many husbands to frequent drinking houses, explaining that “we have to fight against… the sin of Intemperance”.9 The blame for this rise in intemperance lies at least partly with the wives at home:

If only we would keep our homes brighter, and cleaner, and happier, the public-houses wouldn’t be so full in the evenings as they are now… if you all rose early and worked well during the day you would be dressed and ready to receive your husbands and sons pleasantly when they come in from their work.10

A bright and clean home, a pleasant and healthy wife, and a full schedule of activities for the children: if Stephenson were alive today, I wonder if she might finally find her perfect mother scrolling through Instagram!

The Physical Training of Children (1871)

The Physical Training of Children is a more substantial work, being one of several advice books relating to motherhood and childhood written by the British surgeon Pye Henry Chavasse. Chavasse writes for a wealthy audience—his world is one of wet nurses, fine clothes, and pony riding—but, despite this, his books proved popular and were translated into several different European languages.11

If Chavasse were writing today, he’d certainly find fans on Substack. In The Physical Training of Children, he stands out as a staunch advocate for free play. Rigorous outdoor play in clean country air is best and, while he advises that mothers should supervise their children, he is clear that parents should not interfere with play nor direct a child’s activities:

Do not be always interfering with his pursuits… Remember, what may be amusing to you may be distasteful to him… do not dim the bright sunshine of his early life by constantly checking and thwarting him.12

Chavasse believed that the children of his day were not given nearly enough time to play. The reasons he identifies for this state of affairs include schoolwork, lack of space to play, and books. In a section headed Amusements he states in no uncertain terms that children should not be allowed to spend all day looking at books:

Let the amusements of a child be as much as possible out of doors; let him spend the greater part of every day in the open air… let him be what nature intended him to be—a happy, laughing, joyous child. Do not let him be always poring over books.13

He even quotes the Wordsworth poem ‘The Tables Turned’, which describes the natural world as a much better teacher than any book:

Books! ’tis a dull and endless strife,

Come, hear the woodland linnet!

How sweet his music! On my life

There’s more of wisdom in it.

…One impulse from a vernal wood,

May teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

In order to give children the space to play, Chavasse recommends that a large plot of ground should be set aside in every town and village:

It would be well, in every village, and in the outskirts of every town, if a large plot of ground were set apart for children to play in… Play is absolutely necessary to a child’s very existence… but in many parts of England where is he to have it? Play-grounds and play are the best schools we have; they teach a great deal not taught elsewhere.14

He also laments that many parents insist on making Sunday a “day of gloom”.15 In Victorian England, it was widely considered improper for children to play on a Sunday.16 They were instead expected to attend a Sunday School at the village Church and were only permitted to engage in sedate, quiet activities afterwards or to play with religiously-themed toys.17

The final threat to play is schooling, and this is where Chavasse gets most passionate. Responding to the question “At what age do you advise my child to begin his course of education?”, he writes:

Figs! Fiddlesticks! about courses of education and regular lessons for a child!… Let him have a course of education in play… Begin his lessons! Begin brain-work, and make an idiot of him! Oh! for shame, ye mothers! You who pretend to love your children so much… injure their brains… And all for what? To make prodigies of them! Forsooth! to make fools of them in the end.18

Another section that struck me for its resonance to current discourse is one which seems to discuss the mental health of adolescent girls. It begins by posing the question: “What are the causes of so many young ladies of the present day being weak, nervous, and unhappy?”19 In response, Chavasse prescribes more fresh air, exercise, useful occupation, and greater self-reliance.

Are Modern Parents the Most Anxious in History?

The idea that parenting experts are a recent phenomenon is related to another narrative popular at the moment: that modern parents are the most anxious in history. Parents of the past were carefree—so the myth goes—sending their children out to roam field and copse with naught but a sandwich in their pocket. But I’d like to challenge this idea, too.

When we look beyond the sections on amusements and education, we find Chavasse’s work dedicated primarily to giving advice on health and illness. Indeed, many parenting advice manuals from the nineteenth century are medical compendiums, containing remedies and recipes to ease common health complaints. The Physical Training of Children contains advice for curing or easing a range of illnesses including colds, fevers, consumption, scrofula, chlorosis, and hysterics.

Chavasse also advises on how to avoid such illnesses in the first place through the correct clothing, diet, and exercise. Reading these sections, the picture that emerges of parenthood in times gone by is not one of few cares, but one in which parents worried intensely about things that might make their child ill. Do single-breasted waistcoats make a boy more susceptible to tuberculosis?20 Do cold, wet feet cause bronchitis?21 Can tight lacing lead to a case of hysterics?22 Will washing my newborn’s head with brandy prevent a cold?23 At several points Chavasse even advises parents to consider the direction of the wind before sending their children outside to exercise:

Particular attention ought to be paid to the point the wind is in, as he should not be allowed to go out if it is either in the north, in the east, or in the northeast; the latter is more especially dangerous.24

After reading these books, I wonder if parents have always been anxious about the best way to raise their children; about what may harm them and what may help them. While the things parents worry about change; it is perhaps a fact of life that parents contemplate and seek advice on these topics.

I’ll end this section with a final extract from The Physical Training of Children in which we again see Chavasse get passionate, but this time about the ills of a terrible new invention—the pram:

A perambulator is very apt to make a child stoop, and to make him both crooked and round-shouldered… It is painful to notice a babe a few months old in one of these new-fangled carriages. His little head is bobbing about, first on one side and then on the other—at one moment it is dropping on his chest, the next it is forcibly jolted behind: he looks, and doubtless feels, wretched and uncomfortable… the very picture of misery.25

While I approve of Chavasse’s take on play, I don’t think I’ll be giving up my toddler’s Mountain Buggy anytime soon.

Is Local Knowledge more Valuable than Expertise?

Finally, I’d like to address another idea implicit in this narrative: that people with access to cumulative local knowledge have no need of experts. In the first edition of the Physical Training of Children, an introduction written by F. H. Getchell outlines Chavasse’s motivations for writing the book. He begins by reflecting on the reality of child mortality:

The alarming mortality of childhood, amounting to nearly half the children born, before the age of five years is reached, leads us to inquire whether it is an unavoidable fatality of our race…. or… the result of ignorance on the part of those to whom the care of the infant man is intrusted?26

He concludes the latter. Ignorance is the cause and, notably, Getchell states that a mother’s appeals to those around her for guidance often do more to hinder than help:

The sole cause of the difficulty is that the mother has never been instructed… and now that she finds the life and welfare of her offspring dependant on her care and management, she applies to her friends for assistance and receives advice of so contradictory a nature that she is ready to give up in despair.27

Thus Chavasse didn't write his book to plug a growing gap in experience of child-rearing, but as a response to a state of over-information caused by a sole reliance on local knowledge. Chavasse, and other parenting experts like him, offered an authoritative voice able to cut through the noise of contradictory suggestions from friends and relatives.

This picture of a mother so overwhelmed with advice from different sources is one that will resonate with many parents today as they navigate the avalanche of online and offline guidance available. One suggestion I was given as a new mother to counter this overload was to choose just one book about pregnancy and birth to act as sole authority.

This is advice I've found useful for other things too, like learning to bake bread—following the method outlined in a single professional baker’s book is much less exhausting than filtering through the thousands of good and bad methods posted online.

But you don’t have to listen to me—I’m no parenting expert!

This idea was repeated in Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation and has since been circulating on Substack, which inspired this post.

Alison Gopnik, The Gardener and the Carpenter (2016), pp. 28-29.

Gopnik, Gardener and Carpenter, p. 28. The Merriam-Webster online dictionary now gives 1918 as the first recorded usage.

Mrs. Robert Stephenson, Maidenhood and Motherhood, p. 33.

Stephenson, Motherhood, pp. 34-35.

Stephenson, Motherhood, p. 35.

Stephenson, Motherhood, p. 47.

Stephenson, Motherhood, p. 45.

Stephenson, Motherhood, p. 51.

Stephenson, Motherhood, p. 51-52.

Obituary: Pye Henry Chavasse, The British Medical Journal Vol. 2:978 (Sep. 27, 1879), p. 521.

Pye Henry Chavasse, The Physical Training of Children (1871), p. 156.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 155.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 160.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 159.

https://www.exploringsurreyspast.org.uk/themes/learning/families/the-victorians/victorian-childhood/

This belief persisted even after the Victorian era—my octogenarian neighbour remembers the swings our local park being chained up on Sundays!

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 162.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 340.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 283.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 284.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 345.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 21.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, p. 325.

Chavasse, Physical Training of Children, pp. 152-153.

F. H. Getchell, Introduction to The Physical Training of Children by Pye Henry Chavasse, p. v.

Getchell, Introduction to The Physical Training of Children, p. vi.