The Anxious Generation's Inaccurate Tech Timeline

If screentime causes anxiety, why were Millennial teens fine?

The first chapter of Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation makes for alarming reading. Through a series of graphs, it demonstrates that the mental health of teenagers across the Anglosphere declined suddenly and significantly in the early 2010s.1 The book argues that this decline was caused by two interwoven factors: restrictions on free play which have gradually locked children and teenagers into an ever-increasing amount of adult-directed activity; and the rise of the internet-connected smartphone and social media which have increasingly enticed young people away from real-world experiences.

But as a millennial reader, something else about the data caught my eye: between 2000 and 2009, teen mental health was stable—perhaps even slightly improving. This is mentioned in several passages:

Personal computers and internet access… could be found in most homes by 2001. Over the next ten years, there was no decline in teen mental health. Millennial teens… were slightly happier, on average, than Gen X had been when they were teens.

There was little sign of an impending mental illness crisis among adolescents in the 2000s

As boys… began spending more time at home on screens, their mental health did not decline in the 1990s and 2000s

In other words, something was going right for teenagers in the noughties. This is important because it means that if we can compare a millennial adolescence to a Gen Z adolescence, we might gain some insight into “what went wrong” for Gen Z. To make such a comparison, we must begin with an accurate picture of millennial teen life.

So, what was life like for those of us who were teens in the noughties? In Haidt’s retelling, this was a decade in which teenagers occasionally logged on to the internet via the family PC for some rudimentary web-surfing, never straying too far from the safe corners of the internet owing to the parent ever-present in the room who glanced at the screen from time to time. He seems unaware of desktop-based instant messaging and Web 2.0; and makes only one brief mention of the early social media site Myspace. He also downplays the centrality of mobiles, stating that noughties teens spent little time on their phones.

The aim of this article is to give a more accurate account of the ways in which teenagers engaged with mobile phones, the internet, and social media between 2000-2010. My intention is to demonstrate that if poor mental health for teenagers is caused by these activities, then the uptick in mental health problems would begin gradually from as early as 2005—not in the 2010s. Finally, I raise some new, tentative suggestions about how the arrival of the smartphone changed the lives of teenagers.

The Real History of Millennial Teen Life #1: Texting

Let’s start with a claim that will raise many a millennial eyebrow:

“In 2007, teens and many preteens were busy tapping out short texts on their phones, but texting was cumbersome… Most of their texts were with one person at a time, and most used their basic phones to arrange ways to meet up in person. Nobody wanted to spend three consecutive hours texting”.

This passage demonstrates the difficulty of writing an international history of technology. While it is true that texting did not take off significantly in the USA, it was much more popular in Europe—particularly in Britain, where it was a fully-fledged panic-inducing tween and teen craze as early as 2001.2

We British millennials were regularly accused of being glued to our phones. We texted under the desk at school. We texted while waiting at the bus stop. We texted at the dinner table (until we were told to put our phones away). When millennial tweens got together, we bragged about the fastest we’d ever burned through £10 credit. Then, we compared Snake high scores.

This excitement is well-captured in a 2001 article from The Times, titled “ITZ GD 2 TXT”, in which eight children aged eleven to thirteen are interviewed about their mobile phone usage.3 It highlights the near-constant presence of these phones in the teens’ lives and offers insight into why mobiles were seen as desirable:

These children, like more than three million others, are passionate, obsessed about mobiles… They all spend “at least” three hours every day mostly text messaging friends.

“I keep my phone with me all the time. I never know when a new message might come through,” says Natalie Sayer. The children all hold their mobiles even if they’re not using them—for example when watching television.

Day to day… the phones are mostly used for compulsive, continuous texting… All these written, rather than verbal communications, have apparently added to the Edgeware children’s friendships.

“Mobiles are popular because we see them as private, not belonging to parents or siblings”

While teens in this decade did text each other to arrange face-to-face meetups, we also texted just to chat. The 160-character limit and cost of credit meant that we used a new, heavily abbreviated language that omitted most vowels and sometimes substituted sounds or whole words for numbers (Gr8 meant ‘Great’, 2 could be ‘to’ or ‘too’). We texted so often in this way that some academics were genuinely concerned that we’d never learn to speak English properly and the language would be irrevocably damaged as a result.4

We even took our mobiles to bed with us, texting late into the night under the duvet. As one interviewee from the Times article explained:

One night I couldn’t sleep so I texted my friend “R U awake?” and we texted each other to sleep… it’s reassuring to talk to friends.

This tendency was later lamented in a 2006 article in the same newspaper by Sally O’Reilly called “Bring Back Bedtime”.5 The article explores the reasons why teenagers’ bedtimes were getting later and expresses concerns about our plugged-in lives and the ill-effects electronic devices might be having on sleep:

Bedrooms are not synonymous with sleep… Twenty-first century boys and girls are plugged into PlayStations, iPods, and TV. Bedtime, like childhood itself, has turned toxic.

Dr Lucinda Wiggs… says it's a good idea to steer children away from electronic entertainments just before bed. “Over the past twenty years... children are going to bed later. IT is one of the key factors. One survey showed that children are sleeping with their mobiles in their bedrooms—and if they get a text message just as they are falling asleep, it is stimulating”.

There you have it: receiving an SMS on your black-and-white, 96-by-68-pixel Nokia 1600 was “stimulating”!

The Real History of Millennial Teen Life #2: Desktop-Based Instant Messaging and the World Wide Web.6

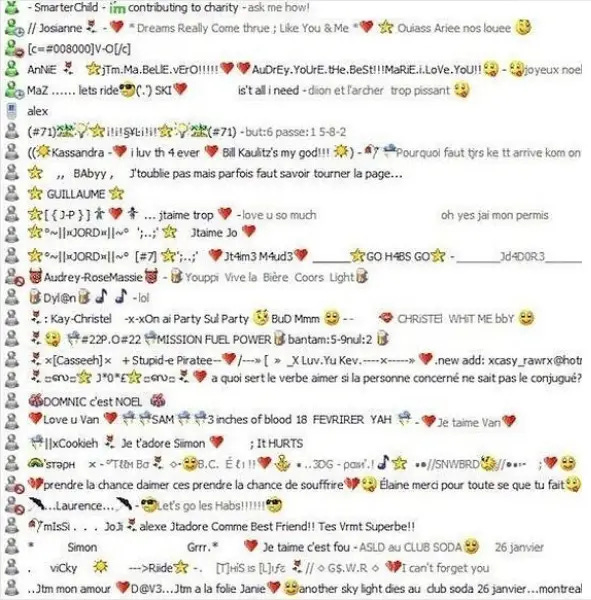

For all the hours we spent frantically tapping the buttons on our phones, mobiles were not the millennial teen's favourite method of communication. A significant amount of our out-of-school social interaction took place behind a screen via a method Haidt seems completely unaware of: the instant messaging programmes on our desktop computers, namely MSN or AIM.

Instant messaging was popular both in Europe and the USA. Many of us logged on everyday after school and chatted for hours. We spoke to multiple friends simultaneously in one-on-one conversations, whilst also maintaining a number of group chats with several participants. Many millennials will remember the sheer glee of having so many conversations flash orange and chime at once that it would momentarily freeze the computer. Parents of millennial teens may recall the distant sound of frantic typing interspersed with sudden eruptions suppressed laughter.

On MSN we talked about our days at school; what films and music we liked; and our lives at home. We asked people out, broke up, confronted each other, and made up again.7 We were kind to each other and cruel to each other. We shared jpeg, GIF, and mp3 files. We played games together. We forwarded chain emails containing quizzes, ghost stories, or messages of good luck. MSN improved the social lives of teens like myself who attended schools with large catchment areas and thus had friends who lived many miles away.

As a result, almost all of my significant teen friendships were made or cemented with MSN. This was particularly beneficial in middle school, where I'd initially struggled to find a group of friends I fit in with. MSN allowed me to nurture friendships with girls and boy who weren't in my classes. I'm still best friends with a girl I was first introduced to on MSN. Another friend, Louisa, married her high school boyfriend—their relationship having been initially kindled by several evenings talking on MSN until the early hours.

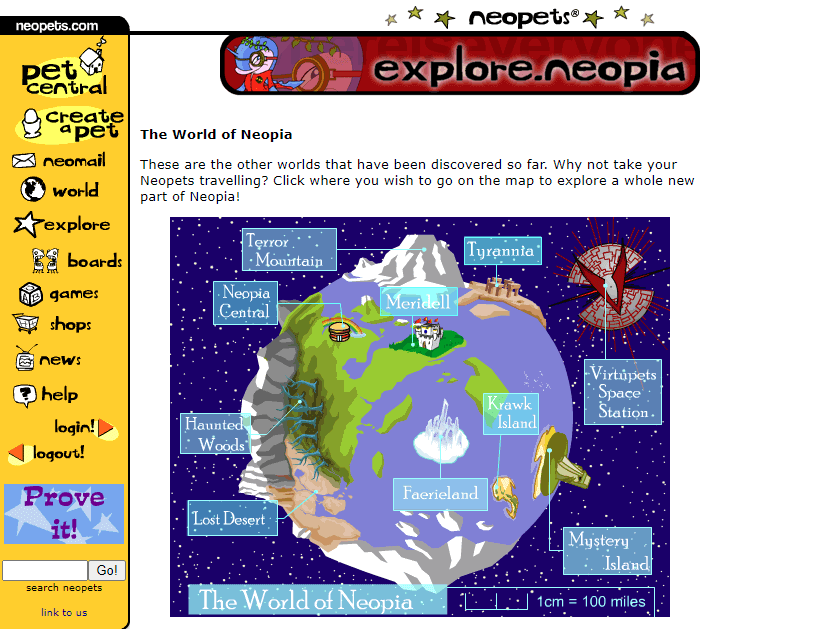

We didn’t just talk on MSN, we also explored the web together by exchanging links to fun, interesting, novel, or scary websites. We played internet games (in my case, Neopets), watched flash animations (such as Weebl and Bob), read webcomics, posted on message boards, and downloaded music. We tricked each other into watching jump-scare videos and dared each other to visit murkier corners of the web (I’m still unsure as to whether penisland.com is a stationary website or porn). We also blogged about our lives and interests, connecting with both friends and strangers on sites like Livejournal.

The best way I can think to describe MSN and the internet in this era is as a vast unsupervised youth club. It was a place where teens could get together in large groups easily and casually. Yes, we were on the desktop computer in the living room—but this didn’t mean we were supervised. Our parents tended to be elsewhere: at work, in the kitchen, or (as we got older) in bed. If they did approach, we were adept at pressing “space, enter, space, enter” quickly to force the conversation out of view (or switching to the Google homepage)—thus avoiding any interference over trivial teen things that adults often overreact about like swearing, slang, talking about crushes, or inappropriate jokes. Our MSN conversations and online lives felt deeply private and it was important to us that we maintained that privacy.

The Real History of Millennial Teen Life #3: Early Social Media Sites

Many of the conclusions reached in The Anxious Generation rest on the idea that social media became suddenly and rapidly popular amongst teenagers with the introduction of the smartphone. Specifically, Haidt cites the addition of a front-facing camera to the iphone 4 (2010) and the acquisition of Instagram by Facebook (2012) as the start-points of “selfie culture”—an online environment in which teenagers upload heavily edited photographs of themselves to the internet for their peers to judge through likes and comments.

Haidt gets the dates correct but misinterprets what they signify. The iPhone 4 didn’t create “selfie culture” by adding a front-facing camera—it added a front-facing camera because there was demand for it. By 2010, teenagers had been uploading edited photos of themselves to social networking sites for at least five years.

I joined MySpace in 2006, and selfies were already a central part of the site’s culture. For a perfect illustration of what a bored teenager might be doing on a quiet Sunday afternoon in noughties, see the first minute of Myspace: the Movie (2006):

Donning our coolest clothes and brushing our hair over one eye, we borrowed the family digital camera and locked ourselves in our bedrooms to take selfies—or, as we called them then, Myspace pics. We also edited these photos with the tools available to us. Most girls knew that if you took a photo with the flash on, turned it to black and white, then upped the contrast, your skin would look flawless. We uploaded these photographs to Myspace for our peers to see and comment on.

On MySpace you could leave comments on your friends' pictures, send direct private messages, post bulletins, or leave comments on a person’s profile page. It was exciting to log in and see the little multicoloured alerts on the left hand side of the pane. There was no feed, so you navigated to other people’s profiles in whatever order you wanted. There was no ‘like’ button, but we could discern who was “cool” based on how much other teens interacted with their profile. A few people were Myspace famous, which simply meant that you had a profile that lots of people checked. But Myspace, in my experience, never felt pressured or competitive. It was about identity and self-expression: carving out your individuality through music, images and questionable HTML choices.

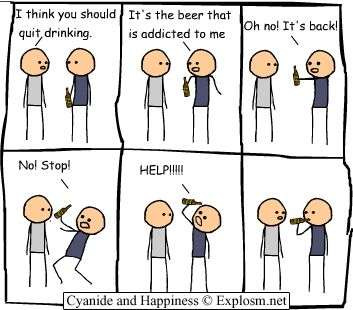

There were concerns at the time that MySpace might be addictive for young people. For example, in December 2005 The Guardian ran an article titled “Welcome to Myspace: it’s fun and it's sexy, but it's highly addictive.” The article raises concerns about “a generation of teenagers for whom the line between online and real world interaction is practically non-existent” who are “posting provocative pictures of themselves” online. It quotes a young woman who recalls that when she first joined, “I would realise it had been hours and hours that I had been on the computer talking to all these random people”.

The Teen Landscape of the Early Internet: an Online World of Free Play

Peter Gray has argued that the arrival of video games in the 90s provided teenagers with a renewed opportunity to engage in free play, even suggesting this may have contributed to a decline in the suicide rate among boys in the same period. I would like to argue that mobile phones, instant messaging, online games, Web 2.0 and early social media sites functioned similarly in the noughties. These platforms worked together to provide teens with a novel space for free play: a new, exciting world to explore which our parents’ didn’t know much about or interfere with. A space where we built the culture ourselves. As we explored this new world we found territories we liked but also ventured at times into territories we didn't like. Sometimes we came across age-inappropriate or otherwise unsettling content and we learned to deal with it.

This landscape of free play is the reason why, when we met in person, millennial teens often chose to go online together. Again, we can turn to MySpace: The Movie for an accurate representation of the internet-connected desktop PC as a side-by-side social activity for noughties teens. Both chapter one and chapter three show two teenagers sitting at the computer: one on the comfy office chair, the other on a wooden chair repurposed from the dining room. The person in the office chair controlled the mouse, while both could access the keyboard and suggest what to do, watch, or type next.

Note as well that both scenes show teenagers using Desktop computers in bedrooms without any adults in sight—by the mid to late noughties it was increasingly common to have computers in other rooms in the house, or even a designated "computer room" as we called it then.8

Now I realise I'm at some risk of over-correcting, so I will reassure older readers that we did do various non-screen activities too. We talked, baked cakes, walked to nowhere in particular, went into the city to look round the shops, went camping, and dared anyone who looked old enough to attempt to buy alcohol in the vain hope we could get drunk in the park. It depended on the day and what mood we were in.

But screen-time in the form of online games, social media, exploring the web, contributing to online communities, and instant messaging was a hugely significant part of our adolescent years. If talking to friends and playing games online makes you lonelier; and if sharing edited photos (and viewings those of peers) makes you anxious; and if staying up late exchanging messages makes you depressed, then we would expect to see a gradual uptick in teen mental health problems starting in the mid noughties—but we don't.

And yet something did change about the lives of teenagers suddenly and significantly in the early 2010s.

Their parents got smartphones.

The Internet in the 2010s: The Rise of Facebook and the End of Online Free Play

The smartphone did not make social media suddenly and rapidly popular amongst teenagers, the smartphone made social media suddenly and rapidly popular amongst adults.

Smartphones were hugely expensive when first released and thus were cost-prohibitive for most teenagers. This video shows a queue outside an Apple store prior to the release of the first iPhone (2007). We see primarily adults milling around in line:

Similarly, this 2013 piece from the BBC shows the queues for the iPhone 5s. We see some young people, but only one I’d describe as a teenager (in line with his Dad). The 3,000-strong line appears to be populated almost entirely by adult men:

Of course, there have always been adults on the internet. But early on this was limited to those with either the time or the passion to sit at a desktop computer. The smartphone meant that many more adults could now connect to the internet via their phone in the small windows of time afforded to them during the day, such as their commute or lunch break. They could scroll news websites whilst waiting to meet a friend; they could check Facebook and Twitter in the kitchen as the kettle boiled.

As adults joined Social Media, our parents, teachers, aunts, and neighbours became increasingly aware of what we were doing online. We were all told we should delete photos of ourselves drunk, lest a future employer see them. Articles appeared in newspapers which stoked panic about the games we were playing including planking, neknominate, and the cinnamon challenge.

The 2010s, therefore, is not the era that teenagers went out into the world wide web unsupervised—that was the noughties. The 2010s is the decade in which teenagers found their online activity increasingly monitored and interfered with.

In addition, adults began sharing the offline activities of children and teenagers within their own networks (and often to complete strangers), opening them up to public approval or admonishment from adults. As this 2019 BBC article highlights, many children are uncomfortable with their parents sharing photographs and information about them online:

Konrad Iturbe, a 19-year-old software developer in Spain, told the BBC he had a "big awakening" when he realised his parents had been posting photos of him online. "I really don't like photos of me online anyway - I don't even post photos of myself on my Instagram account - so when I followed my mother and saw them on her profile, I told her to 'take this down, I've not given you permission'."

He says discovering the pictures it felt like a "breach of privacy".

Similarly, in a 2019 article from Fast Company Magazine, teenager Sonia Bokhari describes feelings of “betrayal” when she realised how much her mother and older sister had posted about her online without her permission:

When I turned 13, my mom gave me the green light and I joined Twitter and Facebook. The first place I went, of course, was my mom’s profiles. That’s when I realized that while this might have been the first time I was allowed on social media, it was far from the first time my photos and stories had appeared online. When I saw the pictures that she had been posting on Facebook for years, I felt utterly embarrassed, and deeply betrayed.

There, for anyone to see on her public Facebook account, were all of the embarrassing moments from my childhood: The letter I wrote to the tooth fairy when I was five years old, pictures of me crying when I was a toddler, and even vacation pictures of me when I was 12 and 13… there were hundreds of pictures and stories of me that, would live on the internet forever… I was furious; I felt betrayed and lied to.

Teens get a lot of warnings that we aren’t mature enough to understand that everything we post online is permanent, but parents should also reflect about their use of social media and how it could potentially impact their children’s lives as we become young adults.

There are other ways adult interference manifested behind the scenes in the 2010s too—such as savvy marketers who plied popular teen YouTubers with free products, creating the influencer and the high-comparison culture that goes along with it. As Kate from Embedded has explained, we increasingly found our private internet jokes cropping up in advertising. The emergence of the algorithmic feed is also significant, which essentially allows adults to dictate what teenagers encounter online instead of teenagers choosing for themselves.

The loss of the early internet’s teen landscape marked the end of what was, for many millennials, the Golden Age of the internet.

Online and Offline Safetyism

Haidt is much more convincing on his second topic: the decline of free play. He highlights the problems with ‘safetyism’—a belief that the real world is so dangerous for children that we must never let them out of an adult’s sight. Haidt provides devastating examples of over-protection, such as a school in the USA that won't let children play tag unless they follow adult-imposed rules. He explains that—while we should of course protect children from serious danger—seeking to protect them from any and every harm is likely to do more damage in the long run.

The unavoidable contradiction at the centre of The Anxious Generation is that it is likely to have the effect of replicating in the online world the safetyism Haidt criticises in the offline world. Where once parents were concerned about their children being groomed in chat rooms, they must now also worry that Tiktok will give their child tourette’s syndrome; that learning how to navigate a tablet means they are “wearing smooth” a path in their brain; that Instagram is a shortcut to their daughter getting depression; and that online gaming will make their son a hikikomori.

Stoking these fears is likely to further decrease the amount of time and space teenagers have for free play. For example, several Mumsnet threads (1, 2, 3) demonstrate that some parents are now so afraid of what their offspring might encounter online that they regularly read their child’s messages. Another example is the growing belief amongst parents that screen time is permissible only if it is educational (as decreed by the parent) and only when done with adult supervision. These children may never know the joy of going downstairs early on a Saturday morning to help yourself to breakfast and watch cartoons (and their parent’s may never know the joy of a lie in).

Finally, smart technology has intensified the level of adult direction, interference, and surveillance in the lives of children and teenagers. Haidt does mention this factor at the very end of The Anxious Generation, but his discussion is limited to two paragraphs and is crying out for significantly more exploration. The book cites recent trends in schools to send instant notifications of a child’s behaviour or grades to their parent’s phone as one example of this overreach. Another example is the not uncommon practice of parents using smartphones to continually track their child/teenager’s real-time location. Indeed, Haidt confesses to doing this himself for “family logistics”. This need to constantly know one another’s whereabouts cannot be healthy for parent or child. For the parent, tracking is a crutch that might alleviate their anxiety in the short-term but will prevent them from learning how to control it in the long term (“Will we ever turn it off? Should we? I don’t know the answer”, Haidt muses). For the child, tracking their location at all times sends one clear message: the world outside is dangerous and you are not competent enough to navigate it without a parent in your pocket.

***

In Haidt’s other writings, he has expressed regret that our society seems to be moving away from the ancient wisdoms and aphorisms that once guided us. On this we also agree. Adults: maybe it’s time we remove the log from our own eye.

Jonathan Haidt, The Anxious Generation (2024).

In April 2000, an estimated 360 million texts messages were sent in the UK (‘The Joy of Text’, The Guardian, 03 June 2000). By January 2003, the number had risen to 1.5 billion per month (‘Texting Time’, The Guardian, 13 Jan 2003).

‘ITZ GD 2 TXT’, Tim Teeman, The Times Weekend Supplement, 26 May 2001. As well as capturing the excitement about mobiles, this article also cites some of the concerns people had at the time about potential health effects. It quotes a government-sponsered report which warned that “Children are likely to be more vulnerble… to potentially hazardous agents… Because of their smaller heads… children may absorb more energy from a phone than adults.”

See, for instance, ‘How talking in text could wreck our children's grammar’, The Daily Mail, 23 January 2001; and ‘Last Word in Texting’, The Daily Mail, 12 July 2001.

‘Bring Back Bedtime’, Sally O’Reilly, The Times, 7 Nov. 2006

This section is based heavily on my own experience. For an account of this era from the USA that shares several similarities with my own, see Kyle Chayka’s ‘Coming of Age at the Dawn of the Social Internet’ in the New Yorker.

For a delightful hit of MSN nostalgia, see this Buzzfeed post.

These actors could be college student age—I'm not sure—but in my own experience this social use of a desktop was common to younger age groups too.